Connie is a storyteller. She plants seeds; ideas and images that make the mundane and familiar feel strange and

dislocating. Maps of places you thought you knew; dream and myth layered over familiar topography.

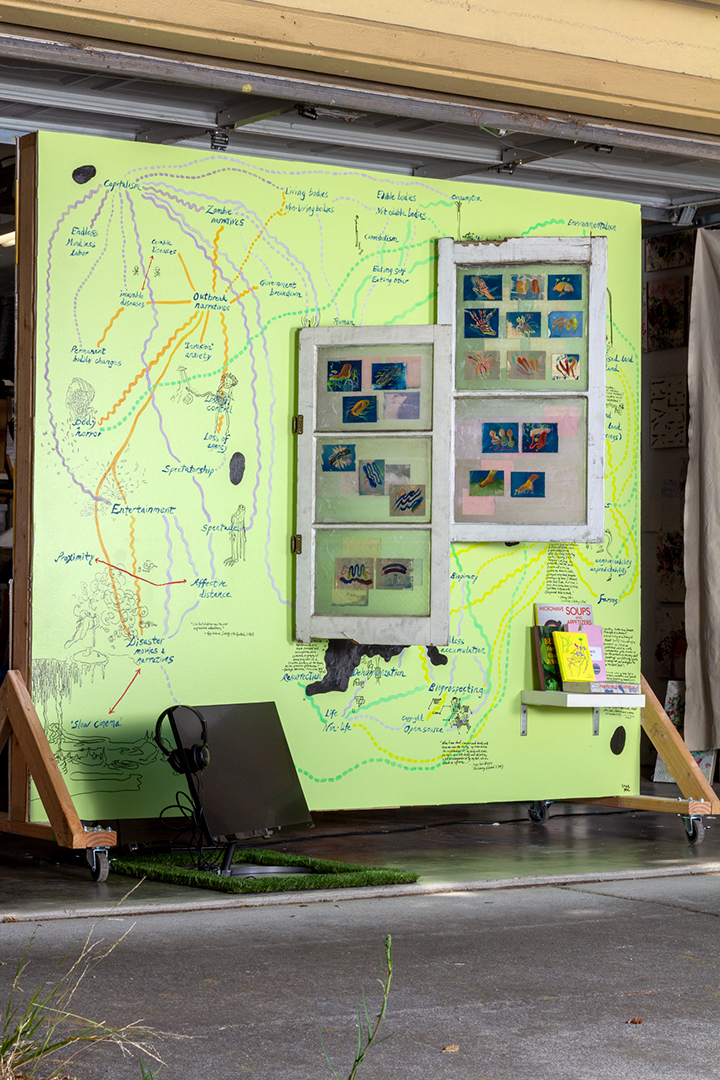

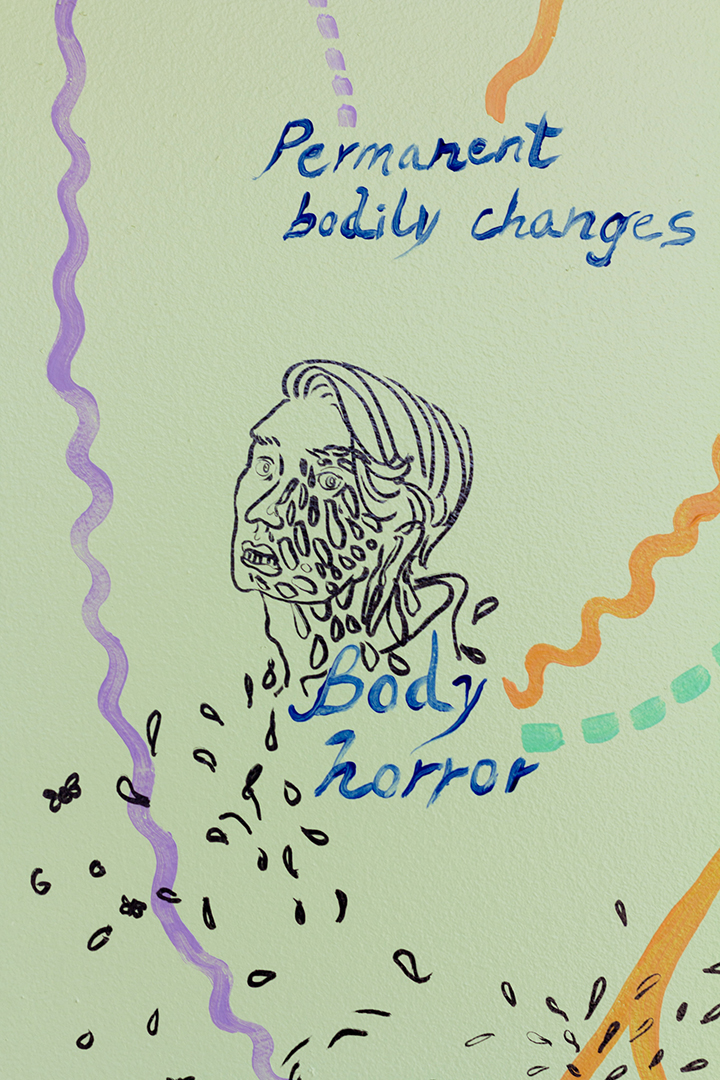

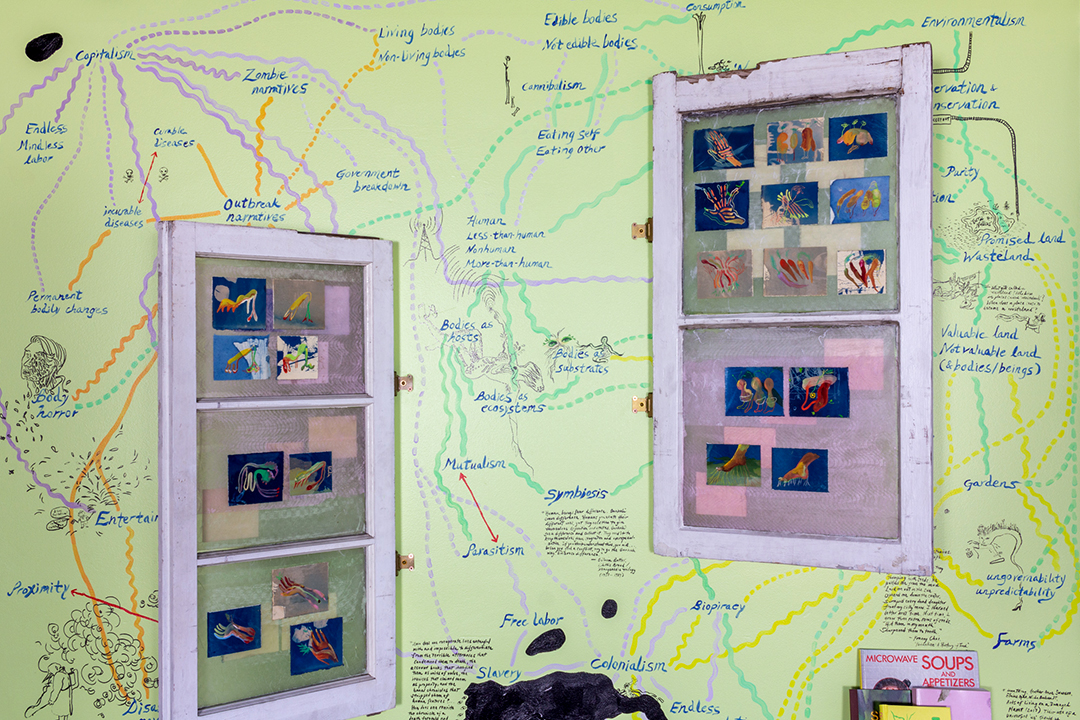

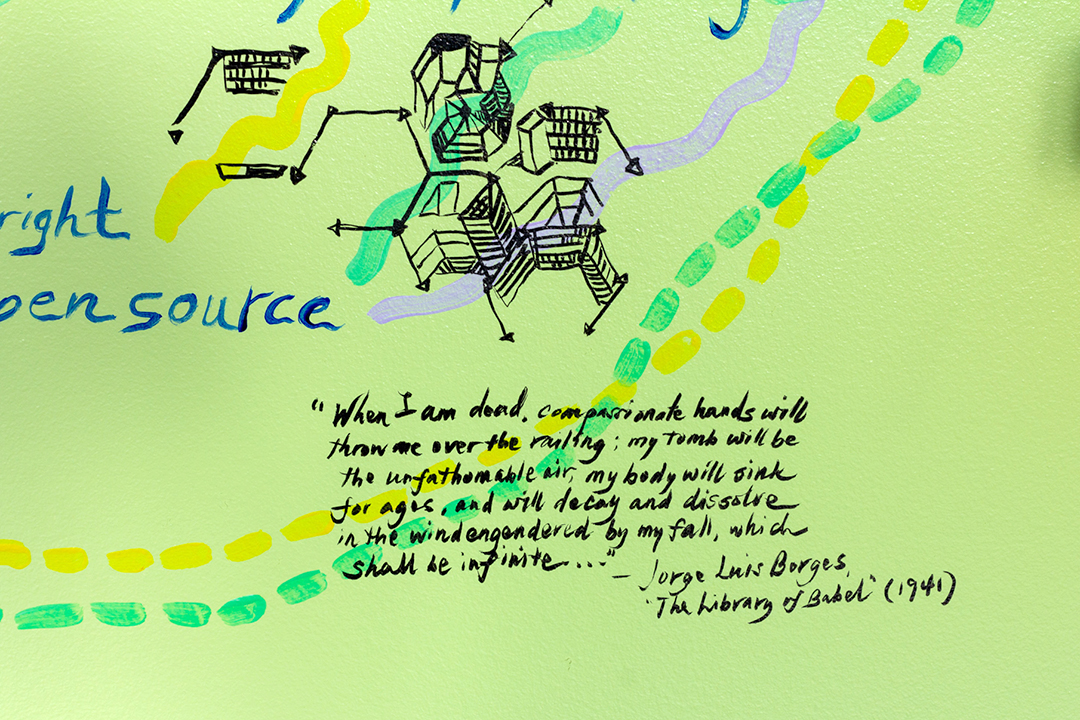

As we traded emails back-and-forth, Connie described the nascent project that would become Terrine as a mindmap

for a graphic novel project about "the banalities and exigencies of late-stage capitalism amidst a zombie apocalypse."

Presented as an arrangement of painted imagery on glass window panes, with hand-painted wall text and images,

Terrine offers a glimpse of a world reimagined: struck by a mundane apocalypse, a populous shrugs off

the horror confronting them at every turn because they still need to pay rent. Through storytelling Connie confronts

climate degradation and capitalist exploitation, while placing audiences in the position of those who keep going,

planting seeds—wherever they can—for the future.

Connie Zheng (b. Luoyang, China) is an artist, writer,

filmmaker, and occasional field recordist based out of xučyun / Oakland, California. She works with maps,

seeds, food and environmental histories, speculative fiction, and experimental film. Her work frequently

includes participatory scenarios and attempts to diagram relationships between human and more-than-human worlds,

as well as the concepts that sustain or destabilize these relationships. Projects such as maps of food plant

migrations, fantastical seed exchanges, seed-making workshops, and improvisational pseudo-documentaries are

strategies for navigating diasporic memory, the continued weight of history, and possibilities for collective

imagining amidst ongoing and future ecological transformations.

conniezheng.com